Crypto’s Incentive Misalignment Problem

Thanks to Jordi Alexander, 0xngmi, Proph3t and Hildobby for reviewing the article and providing feedback, with special thanks to Robin Davids for the brainstorming over the past months.

1. Introduction

In traditional Web2 businesses, significant returns are typically linked to a company's long-term success. Founders and early investors are incentivized to build sustainable businesses because their ability to profit is closely tied to the company's performance over time. In contrast, Web3 often allows some market participants to secure large returns relatively quickly, without requiring the project to achieve PMF or demonstrate real utility, as access to liquidity is much easier. TGEs can occur at any time and do not require the project to meet specific milestones, unlike IPOs in TradFi.

The weak success-exit link in Web3 causes a significant incentive misalignment. Many market participants optimize for short-term returns that do not require a product to be successful in the long term. The lack of transparency and regulation in crypto allows value-extractive behaviors to be profitable and often go unpunished. If this issue is not addressed, it could pose a risk to the growth and adoption of our industry, as value-extractive behaviors will continue to be incentivized and rewarded over long-term, sustainable efforts.

There is no doubt there are plenty of well intentioned people in the space, this article aims to address the issue caused by those who are not.

2. Describing the Incentive Misalignment Problem

Prisoner's Dilemma Leading to the Tragedy of the Commons

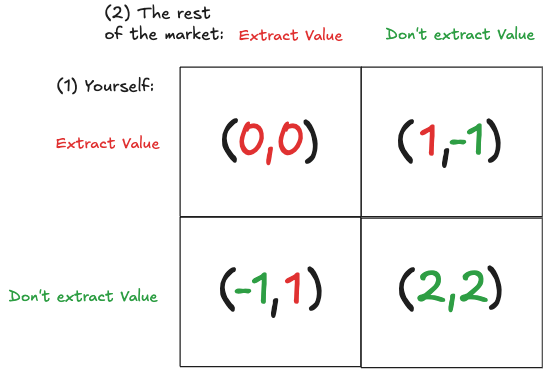

In crypto, market participants often face a dilemma similar to the Prisoner's Dilemma when deciding how to act in various situations.

Examples include a KOL deciding whether to disclose a promotion, a CEX setting criteria for listing a token or determining its launch valuation, a memecoin insider dumping tokens early, or a founder exiting OTC shortly after TGE and abandoning their project. Many opt to extract value for short-term gains, even though this may reduce their potential for long-term returns if the industry grows.

As the Prisoner’s Dilemma keeps happening, it often leads to the Tragedy of the Commons, a theory explaining how individuals acting in self-interest can deplete shared resources, resulting in worse outcomes for everyone. In crypto, these value-extractive actions can misallocate capital and other resources, discourage sustainable projects, and harm the industry’s credibility.

The Logarithmic Utility of Wealth

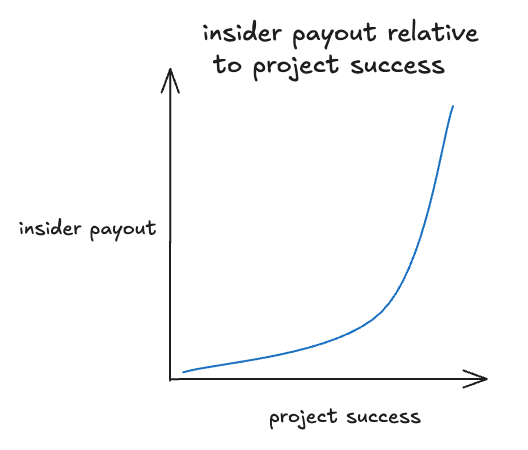

As wealth increases, the marginal utility of additional wealth decreases non-linearly: initial gains significantly improve well-being, but further gains offer diminishing satisfaction. This concept is particularly relevant to crypto market participants when evaluating their incentives.

In many cases, extracting short-term value can lead to significant financial improvement. However, the additional benefits of staying long-term aligned may be less impactful, further incentivizing participants to prioritize short-term gains.

Example: A founder’s token allocation is worth $10 million shortly after TGE but locked for 3 years. Exiting early through OTC at a 60% discount could still generate enough to retire. On the other hand, staying long-term and seeking PMF carries a high risk that the allocation might be worth less than $4 million in 3 years. Even if the project succeeds, providing the chance to exit for much more than $4 million, the founder may still prefer the guaranteed $4 million, as the risk/reward of waiting for higher returns is often not attractive.

“The more successful a project is, the weaker the incentive for insiders to make it even more successful. This explains why we have so many projects that make it from 0 to 1 and then slowly fade.” – Proph3t from MetaDAO

Source: Fixing crypto’s incentives, for fun and for profit - Proph3t

Who Benefits and Who Suffers?

Beneficiaries of Misaligned Incentives

It’s worth noting that generally, those in more privileged positions have the most opportunities to benefit from these incentive misalignments, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone in these groups acts maliciously. There is a spectrum from very well to very bad intentioned participants in each of these groups.

Teams and Founders: They have control over project design, tokenomics, and strategy, which allows for early exits without necessarily ensuring the project's long-term viability.

VCs: Early-stage capital allocation is critical. If VCs can generate higher returns by funding projects that aren’t sustainable in the long term and exiting early, many will likely take that route.

Centralized Exchanges: Their incentives should be aligned with their users, but often we see CEXes extracting value by listing tokens at an inflated valuation, charging significantly high listing fees or listing low quality assets, which goes against their users’ interest.

Market Makers: Some may leverage their advantageous position and teams' need for their services to negotiate highly favorable terms for themselves.

KOLs: We frequently see undisclosed promotions, misleading information, and pump and dumps designed to extract value from their audience in the short term.

In most cases, participants in these groups are incentivized to maximize returns, as they are running businesses. It is therefore reasonable to expect them to act in ways that optimize their profits.

Those Who Suffer

Retail Investors: Often less sophisticated and informed, they become exit liquidity for more sophisticated participants. The lack of transparency combined with the value extractive behaviors of some of these groups, makes it particularly challenging for retail to participate in liquid markets.

Long-Term Participants: Developers, community members, and investors committed to sustainable growth may become disillusioned by the prevalence of short-term behaviors. This can lead to a talent drain and lack of innovation in our industry.

Is the incentive misalignment slowing down the industry progress?

While this is a subjective view, I believe the misalignment of incentives is slowing down the progress of the industry and putting its future at risk. If key market participants adopted a longer-term focus, prioritized sustainable projects, and found it harder to extract value in the short term, the industry would benefit greatly. This topic has been widely researched in industries outside of crypto.

3. The Path Toward Incentive Alignment

Possible Approaches

a) Regulatory Intervention:

The implementation of laws and guidelines to enforce better behavior and ensure transparency would benefit the industry. However, since crypto operates globally and isn’t governed by a single jurisdiction, enforcing effective global regulations is nearly impossible.

Additionally, regulations are beyond our direct control. While we can advocate for them, there’s no guarantee they will be implemented, and they may not favor the industry. Therefore, although the right regulations would be helpful, we cannot rely solely on them to address incentive misalignment, especially in the short to medium term.

b) Doing Nothing and Waiting for Market Self-Correction:

New markets tend to self-correct over time by addressing inefficiencies. However, in crypto, the absence of regulation, transparency, and accountability makes self-correction more challenging. Many participants may not even be aware of the value extraction occurring.

While self-correction plays a role, improvements such as better valuation frameworks are needed. However, without greater transparency, there is a real risk that self-correction may not occur or that it will waste significant time and resources.

c) Encouraging Self-Regulation:

Though self-regulation is difficult to implement and imperfect, it is likely the most practical solution in the short to medium term. It requires the community to advocate for greater transparency, hold participants accountable by exposing bad actors, and foster a culture of ethical behavior. Better self-regulation will likely accelerate the process of market self-correction.

4. Encouraging Self-Regulation: Transparency and Accountability

The Role of Transparency

More transparency is essential to reduce information asymmetry, enable greater accountability against bad actors, and allow the market to self-correct some of its current issues effectively.

Areas Needing Greater Transparency

Founders/VCs:

More transparency on ownership of insiders’ addresses

Disclose OTC sales or hedging strategies

Provide transparency on the team’s commitment, roadmap and progress

CEXes:

Disclose token listing criteria, including listing fees and any relevant terms

Disclose any conflict of interests

Provide transparency about upcoming token listings

Market Makers:

Disclose market-making agreements and any relevant terms

Reveal incentive structures and potential conflicts of interest

Publish activity reports, including any potential market impact

KOLs:

Disclose financial relationships with projects

Declare token holdings or recent purchases when relevant

Reveal paid promotions

Holding Participants Accountable

Community vigilance: Encourage open discussions and critique of unethical behaviors.

Example: Be vocal on CT when a key market participant lacks transparency or engages in value-extractive behavior.

Support those who provide transparency: Both key market participants and independent researchers who make our industry more transparent should be rewarded and incentivized to continue to provide transparency.

Example: Dedicate significant resources to retroactive public funding and grant programs for independent researchers who contribute to making our industry more transparent, ensuring they remain incentivized.

Reputation systems: Build public platforms that allow market participants to access information and be able to tell which key market participants are behaving ethically. This will ensure accountability and prevent value extractors going unnoticed.

Example: Develop neutral agencies to provide public reputation scores for key market participants.

It's worth noting that in some cases, the anonymous identity of some participants can also make accountability more difficult.

5. Improving token vesting designs

Token vesting designs play a key role in shaping market participants’ incentives. The common designs we see today do not address the incentive misalignment problem and, in many cases, facilitate value extraction.

Key design requirements:

Avoid low float at TGE: A reasonable percentage of the supply should be unlocked early, primarily non-insider tokens, with a small portion from insiders as well.

Move away from fixed token supply: Most projects would benefit from flexible, uncapped supply with the ability to mint additional tokens as needed or on an ongoing basis. Fixed supplies are inherited from BTC, most projects have very different characteristics.

Convex payouts for insiders: Align token unlocks with project success to incentivize long-term behavior, similar to TradFi and IPO structures.

Incorporate goal-based unlocks: Not all token unlocks need to be time-based. Milestone-based insider unlocks better align incentives, though certain metrics require caution as they can be gamed. This is an underexplored approach worth experimenting with.

Example: Token vesting for a Team’s allocation in an Ethereum L2

This is just an illustrative example, intended to provide general guidance rather than a precise framework.

20% linear vesting over 4 years: Allows partial selling if needed, which is useful when founders’ locked tokens make up 99% of their net worth. A small cash-out can have a big impact and help maintain long-term focus.

80% goal-based split as follows:

30% Valuation-based: Unlock 1% for every $1 billion in valuation between $1 billion and $10 billion FDV, and 2% for every billion above $10 billion FDV, using a long-term moving average.

20% Delivery-based: For shipping the product (e.g., achieve Stage 2, decentralize the sequencer)

20% Performance-based: For consistent uptime, throughput, and other long-term operational metrics.

10% Metric-based: Based on key metrics such as sticky TVL, revenue, or the number of successful ecosystem apps.

Ongoing Emissions: Linear + Goal-Based:

Linear: 2% yearly emissions to keep the team incentivized.

Goal-based: 3% for every extra $1 billion valuation above $20 billion FDV.

Benefits:

Stronger success-exit correlation: Rewards well-intentioned founders while aligning unlocks with product development and project success.

Harder to exit OTC: If the team wanted to exit OTC and abandon the project, reaching some of the goals could become more challenging, likely resulting in a larger OTC discount and discouraging an early exit.

Clear goals: Transparent, measurable milestones encourage accountability and provide clear targets to work toward.

Challenges:

Prevent manipulation: Some KPIs can be manipulated, so they must be carefully selected.

Enforcement: It would require a decentralized governance process or an objective third party to ensure tokens are unlocked fairly.

Choosing the right goals: Goals should be relevant to the long-term success of the project and reflect varying levels of complexity.

There hasn’t been much testing of goal-based unlocks in our industry so far. Some of the most relevant ones have been:

Algorand: in 2019 updated its vesting from 2 to 5 years but allowing for earlier unlocks based on the token’s valuation.

UMA: in 2021 they airdropped KPI options that could be redeemed based on UMA’s TVL.

Filecoin: part of their vesting is tied to the performance of its storage network.

While these experiments were interesting, none made goal-based unlocks a core part of their vesting design from the beginning, or only allocated a small portion to it. MetaDAO appears to have embraced this concept at its core, and hopefully more teams will experiment with similar approaches.

Is this also applicable to early investor token vestings?

Early investors also need to be aligned with long-term goals but have much less control over achieving specific milestones. A mixed approach might be more suitable for them (e.g., 50-50% linear vs goal-based, rather than 20-80% for the team)

6. Conclusion: A Call to Action

Since we cannot rely entirely on regulations, especially with their uncertain timeline, the community cannot afford to wait for the market to self-correct. While it’s possible that, over time, more projects will achieve PMF, better valuation frameworks will emerge, and respected key participants will lead by example, encouraging others to follow, there are steps we can take now to address the incentive misalignment problem:

Acknowledging the problem: Recognize that misaligned incentives can undermine long-term growth, innovation, and trust in the industry.

Promoting transparency: Demand disclosures and openness from all market participants to reduce information asymmetry and allow more informed decision-making.

Holding bad actors accountable: Encourage community vigilance, support those calling out value extractors and have mechanisms in place to identify them.

Asking for innovation in token vesting designs: Explore ideas such as goal-based unlocks, ongoing emissions, uncapped token supplies, and convex payouts to better align incentives for the long term.

Improvements in these areas will increase the likelihood that more sustainable projects are built and that our industry grows over time.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that I would have liked to conduct a more quantitative analysis of the value extraction in our industry. However, the lack of transparency made accessing much of the relevant data impossible, which reinforces the issues highlighted in this article.